How do men in the ranks handle tough costly battles?

In spring of 1863, starting on April 27th, the Army of the Potomac under Gen. Hooker begin attacking Lee’s forces across the Potomac River in the Chancellorsville Campaign, pursuing a victory that would then allow Union forces to push on to Richmond.

Gen. Hooker had replaced Burnside after the failures of the first Fredericksburg assault in Dec.1862 and then the Mud March Jan.1863. Hooker reorganized and raised moral in the Army of the Potomac, so the men were ready for the spring assault on the rebels. Hooker intended to keep Confederate forces pinned down in Fredericksburg while he outflanked them with a greater force from the west coming through Chancellorsville. Union troops began moving on April 27th. Hard battles with Confederate forces in the distractive assault on Fredericksburg and also around Chancellorsville resulted in Hooker giving up and ordering retreats by May 5th/ 6th. Another gloomy defeat for the Army of the Potomac.

Wilbur Fisk, a Vermont soldier serving in the 6th Corps involved in the assault on Fredericksburg shares his perspective on the campaign to his hometown newspaper in a letter written a few days after they had retreated back across the Potomac for safety. Enjoy this interesting analysis of the failed campaign from a man-in-the-ranks perspective -- yes, it was tough, but do not believe everything you read in the newspapers:

Camp near White Oak Church, Va. May 19, 1863

The smoke of the battle has cleared up [Second Battle of Fredericksburg], giving us a chance to look over the ground and count the cost and consequences of our late bloody campaign. As we are considered fighters by trade, the last attempt in our line of business will have prominence in our thoughts and be the leading topic of conversation till another “rip” comes off. It may be an old story in Vermont by this time but it is not exactly so here. We all have our stories to tell, and where they are deficient in fact we supply the lack from imagination.

|

Marye's Heights Stone Wall

May 3d, 1863

Library of Congress/ Andrew Russel Image |

It is quite amusing to see the accounts the newspapers give of our proceedings here subsequent to coming this side of the river [back north of the Rappahannock]. Hooker, it was coolly said, was over the river again and pursing Lee’s fleeing forces into the last ditch. The Philadelphia Inquirer (I believe) shrewdly observed that the next battle would probably be fought somewhere on the Pamunkey and then the door to Richmond would be thrown open to the victorious Yankees. The backbone of the rebellion, so long on the point of breaking, would be able to sustain the pressure no longer, and the starved-out confederacy would succumb at once, letting peace and prosperity once more shine into that slavery-darkened region, while the Flag of our Union should float triumphantly over all. This looks very fine in print, and if the papers would only fight the battles for us and give us an open road to the rebel capital we should be abundantly satisfied to walk in and make that noted, as well as notorious, city ours. It is vastly easier to win victories on paper than on land, and the experiment has proved that to drive Gen. Lee and his army from the Rappahannock to Richmond is an operation attended with considerable personal danger. We had no idea that we was to start for Richmond again after being drove to this side, till we saw it in some of the leading dailies, and then, it is needless to say, we didn’t believe it.

I noticed the New Jersey papers claim that the 26th New Jersey regiment with the Vermont brigade captured the rebel stronghold on the heights of Fredericksburg. That is strictly true, but it strikes us that the mention of the 26th is entirely gratuitous and unnecessary. It reminds one of the Dutchman who in the excess of his vanity to make a display for himself, boasted that he and the Squire owned forty cows, when it would have been equally true had the “he” been left out, for the forty cows all belonged to the Squire.

But after all, that regiment contains some as brave boys as the country affords, and it is a pity they should have to serve in such a miserable organization. It is not necessary to have the men all cowards to have the regiment break and run. Fear is one of the most contagious diseases that ever afflicted a soldier, and when one timid fellow loses his heart, others are apt to be affected in the same way. It takes a fellow of more than ordinary courage to come up to the scratch when others desert their post to hide away from the bullets of the enemy. Every man that leaves and runs, encourages the enemy, and prompts them to crowd a little harder, and when one after another has skulked away and the ground is getting covered with wounded and dying men, while all the time the enemy are pressing harder and harder and bringing up heavy supports as they did in the second day’s fight, leaving our men no hope of driving them back, but only of holding their ground and gaining time, it takes but a word to start a panic that no power on earth could stop.

No matter how brave a man may be when that event takes place, nor how much he may deplore the event, if the rest run, he must run too, or be overwhelmed.

When the Jerseys broke in the 5th, on Monday afternoon, some of them fell in with us, willingly, and some fell in with the 6th regiment, to show the Vermont boys that they were not a set of cowards, and when that regiment charged, they charged with it, and they kept a long ways ahead, making themselves the most conspicuous mark for the enemy, and plunging first and foremost in every encounter, doing their utmost to retrieve their honor, and the honor of their regiment. Bully for such fellows as that, and all like the, belong to what regiment they will!

The anxious question, when is the Army of the Potomac going to move, has been practically answered. We have moved on to the enemy’s works, and moved off again. We slept one night in the rebels’ nest, and should have slept longer there, perhaps, had we not been forcibly reminded by them that it was a safer place for us this side of the river. Some sanguine writer said, ‘When Gen. Hooker moves on the enemy, God help them;’ but the prayer was unnecessary; they were able to help themselves. On the whole, the most of us are willing to admit that we got a very neat little whipping over there, and General Hooker will have to be more successful than he has been, or his boys will think Old Lee, the rebel General, is too much for him. Our reports claim a sort of victory on whole, and so do the rebels, but the rebel newspapers will lie, and ours won’t. If we accept the rebels’ own calculations that one Southerner is equal to two Yankees, we may safely infer that battles like the last ones pay pretty well, after all; but the rebels can hardly make out as much for them, unless they change the premise of their argument, for they, by no means, killed twice as many of us as we did of them.

Let no one say that the recent battles have had a tendency to demoralize the army. Far from it. The more we get used to being killed, the better we like it. Positively, the army is in just as good fighting spirits to-day as they were the day we left our old camp. I was talking to some New York boys a few minutes ago, whose time of service has nearly expired. The late battles, I found, had not discouraged them in the least, and a large majority said they contemplated re-enlisting after they had enjoyed the luxuries of home a while but they would not bind themselves to any paper at present, preferring to wait and see what would “turn up,” as they expressed it.

Hard Marching Every Day -- The Civil War Letters of Private Wilber Fisk (University Press of Kansas) p.85-87

What?!?” Newspapers do NOT always get the story right?!?

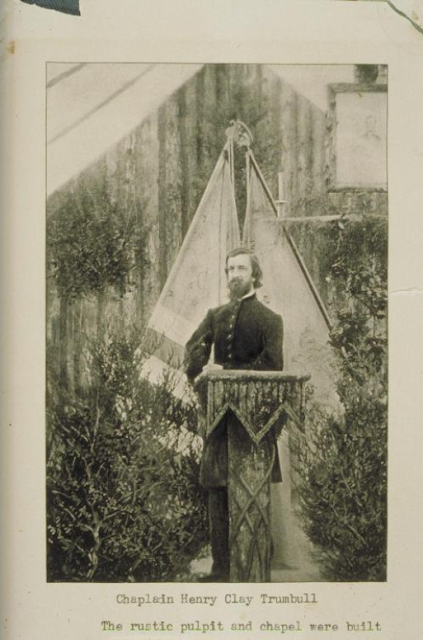

Wilbur Fisk is indeed a gifted writer. Over the course of the war, he wrote many letters to the Green Mountain Freeman newspaper under the name “Anti-rebel.” He was born in Sharon, VT (June 7 1839) and lived until March 12, 1914. Mainly self-educated, he taught in a rural school district for seven terms. 1861 he enlisted in Co.E 2nd Vermont Volunteers. After the war he tried his hand at farming in Kansas for a decade before turning to the ministry and serving as the Congregational pastor in Freeborn, Minnesota, for more than 30 years.

Fisk is writing this letter to his hometown newspaper after he has read how various newspapers are describing the latest failed Union push into Virginia.

Now you may say that Fisk is just rambling on, but as you walk through his analysis of this latest Union failure, catch how he is putting the strategic set-back (big picture) into perspective with explanations of tactical insights (on the ground small pictures). Yes, units did get routed, and there were reasons for that happening, but individuals often stepped up giving their fullest even amidst the harsh defeat. Even though Fisk shares about retreats, he also affirms that the honorable men in the ranks can handle such things and will rise to the challenge again in the future.

Is Fisk “lying” about the moral of the army to whitewash the campaign failure to his hometown people? I honestly think he is trying to explain that even though ‘once again’ the road to Richmond still has not been traveled, many Union soldiers are still committed to finishing the task of putting down the rebellion. He is also trying to give a more realistic perspective to people back home than what they might read in the newspaper headlines. He is trying to balance out the “failure” with “all is not lost.” The newspapers may project big picture victory . . . then oops . . . pushed back across the river in defeat once again!?! Which is it?!? Once again, we see while the soldiers value the newspapers which they get in camp from ‘back home’, they also evaluate the content for accuracy. Fisk is attempting to give better perspective for the readers back home to both “headline grand oversimplification” as well as “local news focus” which downplays the part of other units in the conflict to highlight the favored local unit.

Is Fisk's perspective the 100% true one? I'm not saying that. Fisk's letter is an interesting illustration of the discussions that were certainly happening around the campfires by the men in the ranks all the time about what was going on and why. I really enjoy Fisk's sense of humor that he uses to make his points.

2nd Vermont Volunteers

Mustered in June 1861, becoming part of the Old Vermont Brigade in Sept.1861, they fought in many battles including the first assault on Fredericksburg in 1862. They were also went marching on Burnside’s glorious Mud March in Jan. 1863 (see my post on January 2022 for a humorous tidbit of history on that march). As part of 6th Corps, in the Chancellorsville Campaign sent to keep the Confederate forces pinned down at Fredericksburg while the majority of the Union troops attempted to outflanked the Rebs, on May 3d they assaulted Marye’s Heights, then were involved in the Salem Church battle before retreating back across the Rappahannock as the campaign failed.

A more detailed unit description is given in The Union Army: A history of military Affairs in the Loyal States 1861-65, (Federal Publishing Company, Madison, WI, 1908), p.108-109:

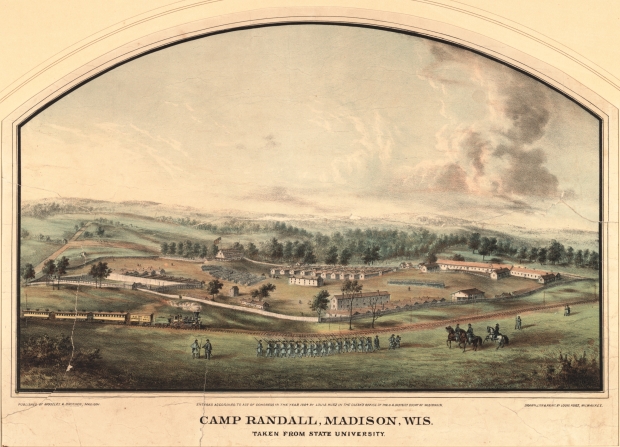

The 2nd Vermont Regiment was organized at Burlington and there mustered into the U. S. service for three years on June 20, 1861. It left Burlington for Washington, June 24, and encamped on Capitol Hill until July 10, when it was ordered to Bush Hill, Va., where it was attached to Howard's brigade, Heintzelman's Division, with which it fought at Bull Run on July 21. It was next sent to Chain bridge for guard duty along the Potomac, and assisted in the construction of Forts Marcy and Ethan Allen. In September it was formed with the 4th and 5th Vermont regiments into the Vermont Brigade (later known on many battlefields), the 2nd brigade of Smith's division.

Winter quarters were established at Camp Griffin and occupied until March 10, 1862, when the regiment marched to Centerville, thence to Alexandria, where it was ordered to Newport News and participated in the Peninsular campaign. It was in action at Young's Mills, Lee's Mills and Williamsburg. In the organization of the 6th Corps, the Vermont Brigade, to which had been added the 6th Vt., became the 2nd brigade, 2nd division. From April 13 to May 19, 1862, the brigade was posted at White House landing. On June 26 it shared in the battle of Golding's farm and in the Seven Days' battles it was repeatedly engaged. It was ordered to Alexandria and to Bull Run late in August. The corps was not ordered into the battle and was next in action at Crampton's Gap and Antietam in September. It fought at Fredericksburg Dec. 13, 1862, after which winter quarters were established near Falmouth and broken for the Chancellorsville battles in May, where the 6th Corps made a gallant charge upon the heights. It fought at Gettysburg, and from Aug. 14 to Sep. 13, 1863, the brigade was stationed in New York to guard against rioting and then rejoined the corps.

Winter quarters were occupied with the Army of the Potomac near the Rapidan and a large number of members of the regiment reenlisted. The command continued in the field as a veteran organization and broke camp May 4, 1864, for the Wilderness campaign. On the opening day of the fight at the Wilderness, Col. Stone was killed and LtCol. Tyler fatally wounded. A number of the bravest officers and men perished in the month following, during which the Vermont Brigade fought valiantly day after day with wonderful endurance, at the famous "bloody angle" at Spotsylvania, at Cold Harbor and in the early assaults on Petersburg. On July 10 it formed a part of the force ordered to hasten to Washington to defend the city against Gen. Early, and shared in the campaign in the Shenandoah Valley which followed - the fatiguing marches and counter-marches and the battles of Charlestown, Fisher's Hill, Winchester and Cedar Creek. During the last named battle the brigade held its ground when it seemed no longer tenable and only withdrew when it was left alone. Returning with the 6th Corps to Petersburg in December, it participated in the charge on March 25, 1865, and the final assault April 2, after which it joined in the pursuit of Lee's army and was active at the battle of Sailor's Creek, April 6, where it is said to have fired the last shot of the 6th Corps.

The service of the 2nd closed with participation in the grand review of the Union armies at Washington, after which it returned to Burlington. The original members who did not reenlist were mustered out on June 29, 1864, the veterans and recruits at Washington, July 15, 1865.

The total strength of the regiment was 1,858 and the loss by death 399, of which number 224 were killed or died of wounds and 175 from other causes. In his well-known work on 'Regimental Losses," Col. Fox mentions the 2nd Vt. infantry among the "three hundred fighting regiments" of the Union army.

Children’s Projects

1) Explore Fisk’s sarcasm about what Newspapers are proclaiming and the realities of the situation for those actually doing the work of fighting the battles. This would be a good occasion to also explore how “media” in its various forms can influence our thoughts and how we have an obligation to evaluate and challenge broad proclamations.

2) Explore how Fisk blends the descriptions of the ‘big picture failure’ with ‘small picture incidents’ to give his readers a better understanding of what is going on at the moment. I find it interesting that he does admit there were serious defeats and retreats, yet courage and commitment was not totally lost individually.

3) It is interesting that Fisk who clearly has excellent writing skills was mainly self-educated. And that he was a teacher in a rural area for several years. Times and expectations have certainly changed. Maybe remind your children that it is what they develop within that will allow them to best use whatever they might get from without.