What might be a creative way to point out the deficiency of army rations to a superior? Here is one interesting account:

While before Petersburg, doing siege work in the summer of 1864, our men had wormy “hardtack,” or ship’s biscuit, served out to them for a time. It was a severe trial, and it taxed the temper of the men. Breaking open the biscuit, and finding live worms in them, they would throw the pieces in the trenches where they were doing duty day by day, although the orders were to keep the trenches clean, for sanitary reasons.

A brigade officer of the day, seeing some of these scraps along our front, called out sharply to our men: “Throw that hardtack out of the trenches.” Then, as the men promptly gathered it up as directed, he added: “Don’t you know that you’ve no business to throw hardtack in the trenches? Haven’t you been told that often enough?” Out from the injured soldier heart there came the reasonable explanation: “We’ve thrown it out two or three times, sir, but it crawls back.”

A brigade officer of the day, seeing some of these scraps along our front, called out sharply to our men: “Throw that hardtack out of the trenches.” Then, as the men promptly gathered it up as directed, he added: “Don’t you know that you’ve no business to throw hardtack in the trenches? Haven’t you been told that often enough?” Out from the injured soldier heart there came the reasonable explanation: “We’ve thrown it out two or three times, sir, but it crawls back.”

[H. C. Trumbull War Memories of an Army Chaplain

(Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York 1898) p.52-53]

I heard this joke about hardtack early on when we started reenacting many years ago, and have often used it myself over the years to explain to spectators, especially kids, about the “glories” of hardtack. No one I talked to knew the source, even though they had heard the joke. Some years later I finally learned the source of the story is from Henry Clay Trumbull, who served as a Chaplain in the 10th Regt. Connecticut Volunteers. Was glad that I confirmed to myself that it had historical background instead of being just a modern reenacting joke.

But what was Trumbull source? Was it his personal slam on hardtack he would tell in a fictional story to make it sound good? The joke about hardtack appears in his book in Chapter 3 entitled “Disclosures of the Soldier Heart”. In this chapter Trumbull uses several incidents which he witnessed to give insight into attitudes and motivation of the soldiers he served with. He cites various incidents of soldiers enduring hardship while still showing great dedication and fortitude in their service to their unit and their country. Then he makes the following summary statement:

“There was no show of heroism on the part of the average soldier, any more than there was a show of sentiment. He simply was a loving-hearted hero, without saying anything about it, or making a demonstration of his feelings. Indeed, a soldier tried to cover up his emotion; and in this effort he would frequently act as if he were ready to laugh, when he felt a good deal more like crying. A joke, indeed, often took the place of an oath, starting a laugh instead of a groan or a sob, as the feelings must find vent in some way.” [p.50]

Trumbull is saying the men he served with were not focused on being famous. Their focus was on diligently doing their duty to comrades and county. Trumbull follows the introductory summary with some examples of how humor helped the men handle the tedium or difficulty of their circumstances. The Petersburg hardtack joke cited above is one of the examples he gives of humor being a vent for frustration.

He then shares a second hardtack joke from the same Petersburg situation:

About the same time, I was accompanying our brigade commander in a tour of observation along our front. As he stopped in the trenches where the men were keeping up a sharp fire, he saw them opening a fresh box of ammunition, of which they constantly needed a new supply. Noting the careful wrapping of the cartridges in their neat packages of a dozen each, he said pleasantly to the soldier who was taking them out:

“’Uncle Sam’ is very careful that his boys shall have good cartridges while in his service.”

“Yes, sir; I wish he was half as careful of their hardtack,” was the keen and respectful reply.

This dry humor in the expression of strong feeling showed itself in the ordinary soldier in every phase of his service.” [p.53]

“’Uncle Sam’ is very careful that his boys shall have good cartridges while in his service.”

“Yes, sir; I wish he was half as careful of their hardtack,” was the keen and respectful reply.

This dry humor in the expression of strong feeling showed itself in the ordinary soldier in every phase of his service.” [p.53]

Trumbull then moves on from examples of humor giving vent to frustration over poor rations to explaining how general humorous contempt toward cowards helped the man in the ranks resist the temptation to shirk his own duty in the next few pages.

Trumbull does not tell how the officers reacted to the hardtack jokes. Possibly his being silent on that aspect might mean the officer in each situation caught the point, knew it was an honest challenge about the poor quality of rations, and chose not to seek punishment on the man who said it. Can’t say for certain.

I do not present this information as being some profound historical discovery to impress you, the reader. I just appreciate knowing the historical background of a joke I’ve often told. And when I tell it to spectators now, I can add the insight which Trumbull gives about humor being a relief for the struggle to deal with difficult challenges like poor quality rations. I have often thought reenacting the incident in front of a crowd of spectators would be ‘humorously educational’.

Henry Clay Trumbull (1830 to 1903) was Chaplain of the 10th Connecticut Infantry starting in 1862. The troops enjoyed his eloquent sermons, his dedication to helping and encouraging them, and his personal courage. He was captured at the battle of Fort Wagner on July 19,1863 while searching for wounded Union soldiers, and held as a prisoner of war until exchanged on Nov.24, 1863, when he then rejoined the 10th Conn., serving with them until they mustered out in Aug. 1865.

After the war, Trumbull became a prominent lecturer, an advocate for Sunday School being incorporated into the American church, and a scholar who wrote many books. Among them was The Knightly Soldier (1865 biography of his friend, Adjutant Henry Ward Camp, who was KIA Darbytown Road, Oct 13, 1865), and War Memories of an Army Chaplain (1898).

|

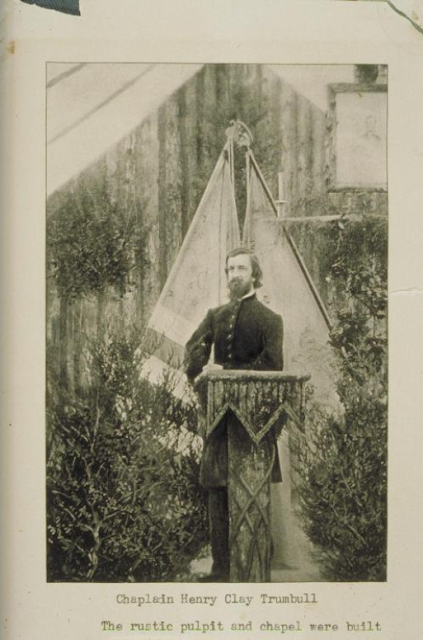

| Chaplain Henry Clay Trumbull Picture from Connecticut Historical Society collection. Rustic pulpit built by Army Engineers below Richmond Va. in the winter of 1864-65. |

The 10th Connecticut Infantry Regiment was one of Connecticut’s most exemplary units, having fought in twenty-three battles and many smaller skirmishes. It was formed in the summer of 1861, serving in the early war coastal campaign from the battle for Roanoke Island to the assault on Fort Wagner, then on to fight in the trench as the Union Army pressed in on Petersburg and Richmond. They were present at Appomattox when Lee surrendered to Grant. The Tenth was one of the top 300 Union regiments in the Civil War (out of over 1,700), according to historian William F. Fox.

Children Projects:

Might be an interesting opportunity to discuss options of handling frustrations. Also, how humor could be better than outright anger, but can also lead to punishment if the superior gets angry. Might look at Proverbs 15:1ff.

For hardtack projects check out my other posts tagged with “hardtack” such as Oct.22, 2022 “Why was hardtack so disdained by the Civil War troops?”

For hardtack projects check out my other posts tagged with “hardtack” such as Oct.22, 2022 “Why was hardtack so disdained by the Civil War troops?”