An account

from a soldier who fought and died there:

The sanguinary

battle of Shiloh was fought on the sixth and the seventh of April, 1862. The ordinary scene which presents itself,

after the strife of arms has ceased, is familiar to everyone. Heaps of the slain, where friend and foe lie

by the side of each other; bodies mangled and bleeding; shrieks of the wounded

and dying, are things which we always associate with the victories and defeats of

war. But seldom do we read that voices

of prayer, that hymns of exultant faith and thanksgiving, have been heard at

such times and in such places.

The

following account was received from the lips of a brave and pious captain in

one of the Western regiments, as some friends who visited Shiloh on the morning

after the battle were conveying him to the hospital.

The man had

been shot through both thighs with a rifle bullet; it was a wound from which he

could not recover. While lying on the

field, he suffered intense agony from thirst.

He supported his head upon his hand, and the rain from heaven was

falling around him. In a short time, a

little pool of water collected near his elbow and he thought if he could only

reach that spot he might allay his raging thirst. He tried to get into a position which would

enable him to obtain a mouthful, at least, of the muddy water; but in vain, and

he must suffer the torture of seeing the means of relief within sight, while

all his efforts were unavailing. “Never”

said he, “did I feel so much the loss of

any earthly blessing. By and by the

shades of night fell around us, and the stars shone out clear and beautiful

above the dark field, where so many had sunk down in death, and so many others

lay wounded, writhing in pain, or faint with the loss of blood. Thus situated, I began to think of the great

God who had given his Son to die a death of agony for me, and that he was in

the heavens to which my eyes were turned, -- That he was there, above that

scene of suffering, and above those glorious stars; and I felt that I was

hastening home to meet him, and praise him there; and I felt that I ought to

praise him then, even wounded as I was, on the battlefield. I could not help singing that beautiful hymn:

And wipe my weeping eyes.

And though I was not aware of it till then,” he said, “it

proved there was a Christian brother in the thicket near me. I could not see him, but was near enough to

hear him. He took up the strain from me;

and beyond him another, and then another, caught the words, and made them

resound far and wide over the terrible battlefield of Shiloh. There was a peculiar echo in the place, and that added to the effect, as we made the night vocal with our hymns of praise

to God.

It is

certain that men animated by such faith have the consciousness of serving God

in serving their country, and that their presence in the army adds to it some

of its most important elements of strength and success.

From Christian

Memorial of the War: Scenes and

Incidents Illustrative of Religious Faith and Principle, Patriotism and Bravery

in Our Army by Horatio B. Hackett 1864 page 18-20.

|

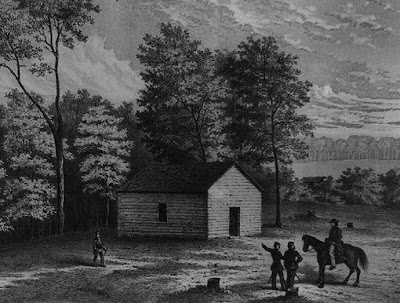

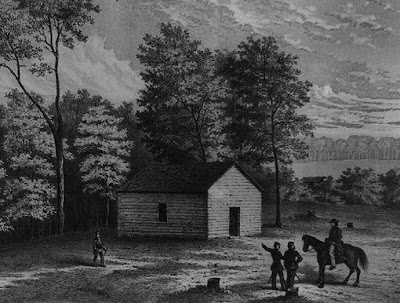

| Shiloh Church |

Summary historical perspective on the battle

The

intensity of the Battle of Shiloh in southwestern Tennessee on April 6-7, 1862,

also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing, changed public expectations in

both the North and the South that this would be a short-lived war because of

the intensity of the battle and the high rate of casualties for both sides:

Union losses

out of 62,000 troops: 13,047

Killed

1,754

Wounded

8,408

Missing

or captured 2,885

Confederate

losses out of 45,000 troops: 10,669

Killed

1,728

Wounded

8,012

Missing

or captured 959

In his memoirs in chapter 25 “Remarks on Shiloh” Grant writes

“Up to the battle of Shiloh, I, as well as thousands of other citizens,

believed that the rebellion against the Government would collapse suddenly and

soon, if a decisive victory could be gained over its armies….” But the

intensity and cost in man-power changed his perspective: “I gave up all idea of saving the Union

except by complete conquest.”

Though the

Union losses were greater than the Confederate, the Union victory would allow

for him to push deeper into Southern territory to divide the Confederacy in

two. Victory came at a high cost.

Reflections on the “soldier in the ranks” perspective on

dealing with the cost of battle

In the midst

of such pain and suffering what should one do?

The above account which Horatio Hackett recounts shows some dealt with

the harshness of their suffering through the lens of faith. The hymn “When I can Read My Title Clear” by

Isaac Watts was first published under the heading "The Hopes of Heaven our

Support under Trials on Earth" in his 1707 Hymns and Spiritual

Songs:

When I can read my title clear

To mansions in the skies,

I’ll bid farewell to every fear,

And wipe my weeping eyes.

Should earth against my soul engage,

And hellish darts be hurled,

Then I can smile at Satan’s rage,

And face a frowning world.

Let cares, like a wild deluge come,

And storms of sorrow fall!

May I but safely reach my home,

My God, my heav’n, my All.

There shall I bathe my weary soul

In seas of heavn’ly rest,

And not a wave of trouble roll

Across my peaceful breast.

“Clear

title” means “undisputed ownership”.

Isaac Watts’ original title -- "The Hopes of Heaven our Support

under Trials on Earth" -- gives us insight into his meaning of this

song. In a world of fear and sorrow, Watts

challenges us to put our trust in Jesus’ promise in John 14:1-3: “Let not your

heart be troubled: ye believe in God, believe also in me. In my Father's house are many mansions: if it

were not so, I would have told you. I go to prepare a place for you. And if I

go and prepare a place for you, I will come again, and receive you unto myself;

that where I am, there ye may be also” (King James Version wording clearly is

the basis for the song). Through faith

in Jesus, Watts says we can put in perspective the troubles of this world as we

look to the place of joy Jesus is preparing for those who trust in Him as Savior.

So there on

the Shiloh battlefield where death, pain and sorrow were abundant, for many of

the men this well-known hymn became a call to look to Jesus’ promise as a way of

dealing with the “storms of sorrow” that night and yet also an offering of

praise to Jesus for His willingness to “die a death of agony for me”. In the Old Testament, the town of Shiloh ("place of peace") became the place where the Tent of Meeting was located after the land was conquered and the people would come to worship God during the time of Joshua and the days of the Judges (Josh.18:1-10). The Shiloh Meeting House on the battle site was built in 1853, and Union forces encamped along the ridge the church was built on. The battlefield took its name from the church. The church was damaged in the fighting, then used as a hospital after the battle, and finally torn down by Union soldiers for the lumber to build a bridge.

In Nothing But Victory -- The Army of the Tennessee 1861-1865 by Steven Woodworth (2005) pages189-191 is a detailed description of the night of April 6. After intense twelve hours of fighting came the darkness with the wounded between the lines "calling for mother, sister, wife, sweetheart, but the most piteous plea was for water". Then came the rain and thunder mixing with the ongoing artillery fire between the lines. Woodworth cites that on one part of the battlefield was heard the singing of Charles Wesley's "Jesus, Lover of My Soul" hymn among the wounded. And elsewhere was the singing of the hymn of this account. I cite this as evidence that the above account recorded by H. Hackett is in fact a description of something that actually happened that night.

Children’s project questions:

1) Talk

about the shift from early war “optimism” that the conflict would be brief and

end soon to the “reality” that it was going to be a “long hard road to

Richmond”. Explore why human nature

often “presumes” desired outcomes more often than realistically thinking

through what might happen and exploring ways to overcome the difficulties to

accomplish the goal.

2) Would

there be many who would join in today if someone started singing a Christian

song on a battlefield filled with wounded & dying soldiers? What does that say about our culture

today? Does that make you glad or sad?